Tag: Digital Literacy

MakEY Makes Deep Connections: Final Thoughts Before My Final Inquiry

My aim at the onset of EDCI: Interactive and Multuimedia Learning had been “to find new and accessible ways to incooperate ideas regarding technology that come from communities outside of North America” (Welcome Post, Sep 2019). However, course readings and resources, sources referenced by classmates, and related articles I came across along the way, have all together led me down a different path.

Here is the evolution of my inquiry questions thus far: How is technology being approached in ECE environments in countries outside N.America? To: Is there evidence of pedagogy that presents digital technology holistically? And finally: Can “Making” support digital literacy in Early Years Education?

During the formulation of my last post, on a hunt for media related to Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (Jenkins et al., 2006), I came across a playful and opinative video that initiated a fresh line of reasoning. Have a watch:

One specific statement made by Jenkins (2009) evoked memories of similar statements made by Galloway with regard to making:

“We learn by failing. We learn by making mistakes, and doing something over, and doing it better. When our schools make failure fatal they cut themselves off from the most vital process of learning there is. That is, learning through our own mistakes, thinking critically at our own behaviour.” -Jenkins

Both in conversation with our class during a recent video chat (Nov 2019), and through her MEd Project (2015), Galloway articulated the importance of a “Growth Mindset” and leaving room for error. In addition, Marsh et al., in their MakEY publication, entitled Makerspaces in the Early Years: A Literature Review, made reference to the value present in failing and the reflection invariably connected to it (Marsh et al., 2017).

The aforementioned connections led to a consideration of other links that might exist between the making presented in both Galloway’s (2015) work and several MakEY project publications (Marsh et al., 2017,2018), and the new media education presented by Jenkins et al. (2006). I began to distinguish similarities amongst philosophies surrounding both creativity and citizenship. Ultimately, the above YouTube video led me to my final inquiry question.

However, before I present my final post connected to Assignment 2 in EDCI: Interactive and Multimedia Learning, I feel it is necessary to provide a short introduction to Making, Makerspaces, and MakEY …

In 2005, Dale Dougherty founded Make Magazine and, some would argue, popularized the term making (Marsh et al., 2017). Dougherty (2013) described the mindset of a maker as one of a growth mindset: a belief that anything can be accomplished as long as one is equipped with the knowledge required to do so (p.10). The Make Magazine, and subsequent Maker Faire in 2006, marked the beginning of the “do it yourself” culture known as the Maker Movement (Marsh et al., 2017). In 2006, innovator and entrepreneur, Mark Hatch, founded Techshop, a for profit makerspace in California, and later wrote The Maker Movement Manifesto (2013). In The Maker Movement Manifesto (2013), Hatch outlines what he considered to be the core principles of the Maker Movement:

MAKE – Making is fundamental to what it means to be human. We must make, create and express ourselves to feel whole. There is something unique about making physical things.

SHARE – Sharing what you have made and what you know about making with others [..]. You cannot make and not share.

GIVE – There are few things more selfless and satisfying than giving away something you have made.

LEARN – You must learn to make. You must always seek to learn more about your making. You may become a journeyman or master craftsman, but you will still learn, want to learn and push yourself to learn new techniques, materials and processes. Building a lifelong learning path ensures a rich and rewarding making life and, importantly, enables one to share.

TOOL UP – You must have access to the right tools for the project to hand. Invest in and develop local access to the tools you need to do the making you want to do.

PLAY – Be playful with what you are making, and you will be surprised, excited and proud of what you discover.

PARTICIPATE – Join the Maker Movement and reach out to those around you […].

SUPPORT – This is a movement, and it requires emotional, intellectual, financial, political and institutional support. The best hope for improving the world is us, and we are responsible for making a better future.

CHANGE – Embrace the change that will naturally occur as you go on the maker journey. Since making is fundamental to what it means to be human, you will become a more complete version of you as you make.

-Hatch, 2013

At its outset, innovation and ingenuity were recognized as key components of maker culture, along with the development of certain craft skills (Marsh et al., 2017), however, today’s maker culture welcomes a myriad of making experiences and represents an inclusive environment within which to create (Schrock, 2014).

Making itself is deeply rooted in the values of constructivism and bears close resemblance to the succeeding constructionist learning theory set forth by Seymour Papert (1980). Making provides space and opportunity for makers to construct knowledge through experiementation, in a space that motivates curiosity, hands-on experiences, and self directed learning (Dewey, 1902). Mistakes and miscalculations are also considered an important part of maker culture as with them comes opportunity to think criticaly, value persistence, overcome difficulties, and generate collaboration amongst learners (Galloway, 2015; Martin, 2015).

Makerspaces refer to collective spaces that supply individuals with an environment to create through hands-on effort. Using the materials at hand, makers are free to work on a project that is either personally or collectively meaningful. In addition, the specific materials provided in a makerspace are considered the “glue” that pulls makers together for collaborative, creative work (Marsh et al.,2017). The teaching-learning practices and demographics within makerspaces are often wide in scope as they include an assortment of ages, genders, levels of understanding and proficiencies (Halverson &Sheridan, 2014). Therefore, makerspaces often promote peer collaboration and introduce fresh perspectives on teacher-learner dynamics (Marsh et al.,2017).

Today, makerspaces are more widely recognized for their educational value, specifically with regard to their ability to promote problem-solving skills and the development of competences connected to engineering, creative design, and innovation (Stager, 2013). In addition, more and more literature is being produced that explores the value of making and makerspaces in the development of digital literacy, including several publications presented by the MakEY project.

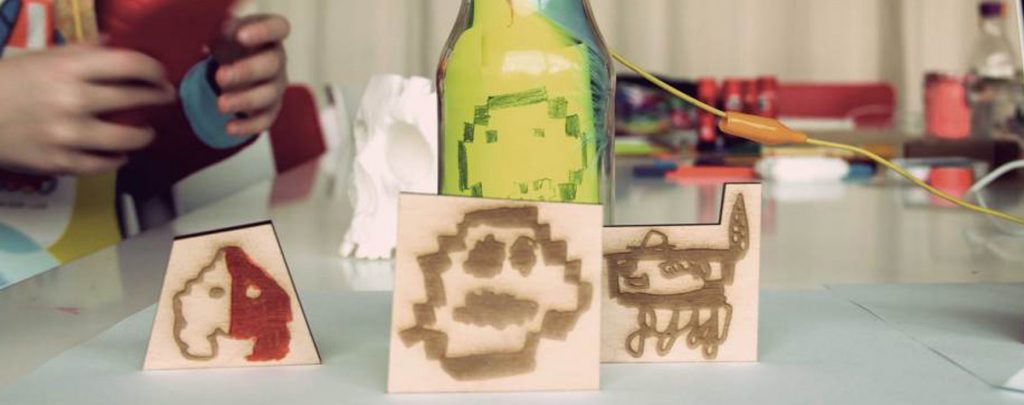

The MakEY project encompasses several small scale, qualitative research projects, in seven European countries and the USA, that aim to examine the way in which making can contribute to children’s digital literacy and creative design skills (“Makey Project”, 2019). All workshops or projects undertaken by MakEY are observed by a team of researchers who utilize recorded observations, field notes, photos and/or video recordings, and, in some cases, footage collected from children wearing GoPro cameras (Marsh et al., 2018).

The few documentations I have observed from MakEY, demonstrate how technology can be incoporated into early learning environments in deep and meaningful ways: the children involved were provided an opportunity to construct knowledge corresponding to their natural environments, their communities, medians (both digital and tactile), and the culture of creating.

MakEY sets forth, as does Galloway (2015) and Jenkins et al. (2006), in their respective works, that intregrating pedagogies connected to design can benefit learners because they encourage mistakes, repetitive operations, and reflection (Marsh et al., 2017).

Until next time. Thanks for reading,

EJ

Up next … Final post connected to Assignment 2 (look for the tag)

References

Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dougherty, D. (2013). The maker mindset. Design, make, play: Growing the next Generation of STEM Innovators, 7–11.

Galloway, A. (2015). Bringing a reggio emilia inspired approach into higher grades- Links to 21st century learning skills and the maker movement. MEd Projects (Curriculum and Instruction): University of Victoria, BC.

Halverson, E.R., & Sheridan, K. (2014). The maker movement in education. Harvard Educational Review, 84(4), p 495–504.

Hatch, M. (2013). The Maker Movement Manifesto. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jenkins, H (2006). Confronting the challenges of Participatory Culture: Media education for the 21st century. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation: Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://www.oapen.org/download/?type=document&docid=1004003

Marsh, J., Arnseth, H.C. and Kumpulainen, K. (2018) Maker Literacies and Maker Citizenship in the MakEY (Makerspaces in the Early Years) Project. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 2(3), 50; https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030050

Marsh, J., Kumpulainen, K., Nisha, B., Velicu, A., Blum-Ross, A., Hyatt, D., Jónsdóttir, S.R., Levy, R., Little, S., Marusteru, G., Ólafsdóttir, M.E., Sandvik, K., Scott, F., Thestrup, K.,Arnseth, H.C., Dýrfjörð, K., Jornet, A., Kjartansdóttir, S.H., Pahl, K., Pétursdóttir, S. and Thorsteinsson, G. (2017) Makerspaces in the Early Years: A Literature Review. University of Sheffield: MakEY Project.

Martin, L. (2015). The promise of the maker movement for education. Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research, 5(1), p 30–39.

Pfbconvergencia. (Oct 12, 2009) Proyecto Facebook [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/MmEFefoe-9U

Schrock, A. (2014). “Educationindisguise”: Culture of a hacker and makerspace. Interactions: UCLA. Journal of Education and Information Studies, 10 (1), p 1-25. Retrieved from: http:// escholarship.org/uc/item/0js1n1qg

Stager, G. S. (2013). Papert’s prison fab lab : Implications for the maker movement and education design. IDC ’13 Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction, p 487–490.

Reframing My Thoughts: Are Frameworks and Philosophies Merely “Slow to React”?

Before I venture further into my inquiry, specifically the “maker movement” and the MakEY Project, I would like to take a moment to reframe and reconsider my thinking thus far. I took a moment to step back, read, and leave room for learning. I discovered that perhaps I needed to look at why, rather than how, digital technology is being addressed by both the BC Early Learning Frameworks and the Reggio Emilia approach to Early Learning.

The first article that altered my focus came in the form of an occasional paper on digital media and learning by Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton, and Robison (2006), entitled Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. I drew an immediate connection from the following excerpt to the frameworks and philosophy I had examined prior:

“Schools as institutions have been slow to react to the emergence of this new participatory culture […] programs must devote more attention to fostering what we call the new media literacies:” -Jenkins et al., 2009

Jenkins et al. (2006) presented two new terms in their report: Participatory Culture and New Media Literacies. Jenkins explains participatory culture and his concerns about education in the following video:

Jenkins et al. (2006) pointed to a growing body of research that suggested that the various forms of participatory culture undertaken by young people outside of school have the potential to generate: “opportunities for peer-to-peer learning, a changed attitude toward intellectual property, the diversification of cultural expression, the development of skills valued in the modern workplace, and a[n…] empowered conception of citizenship” (Jenkins et al., 2006). They also highlighted the fact that many scholars believed that children and youth developed such skills regardless of pedagogical interventions. However, Jenkins et al. believed that three concerns denoted the nescesity for curriculums focused on helping students develop the skills needed to fully participate in, and contribute to, online communities. The three concerns were:

- The Participation Gap — the unequal access to the opportunities, experiences, skills, and knowledge that will prepare youth for full participation in the world of tomorrow.

- The Transparency Problem — The challenges young people face in learning to see clearly the ways that media shape perceptions of the world.

- The Ethics Challenge — The breakdown of traditional forms of professional training and socialization that might prepare young people for their increasingly public roles as media makers and community participants.

Consequently, a central focus of their work aimed to draw attention away from considerations regarding technological access towards opportunities in teaching and learning associated with participating in a digital realm (Jenkins et al, 2006). Unlike the BC Early Learning Curriculums, the primary recommendation by Jenkins et al. (2006) was that an effective pedagogical strategy be developed specifically for media education. However, while reading the report presented by Jenkins et al. (2006), I couldn’t help but notice how many of the New Media Literacies naturally flow into the expectations for deep learning explicated in BC’s New Curriculum (2019) and are instinctively touched on in an approach such as Reggio Emilia.

The three Core Competencies of BC’s New Curriclum are “Thinking (creative,critical), Communication, and Personal and Social”. According the Curriculum Orientation Guide, the Core Competencies are groupings of abilities that learners should develop in order to take part in deep learning. The Competencies should be evident and used when learners are engrossed in “doing” in any area of learning (BC’s New Curriculum, 2019). Consequently, if digital technology is considered an area of learning then learners should be interacting with it in accordance with the Core Competencies and engaging in deep learning.

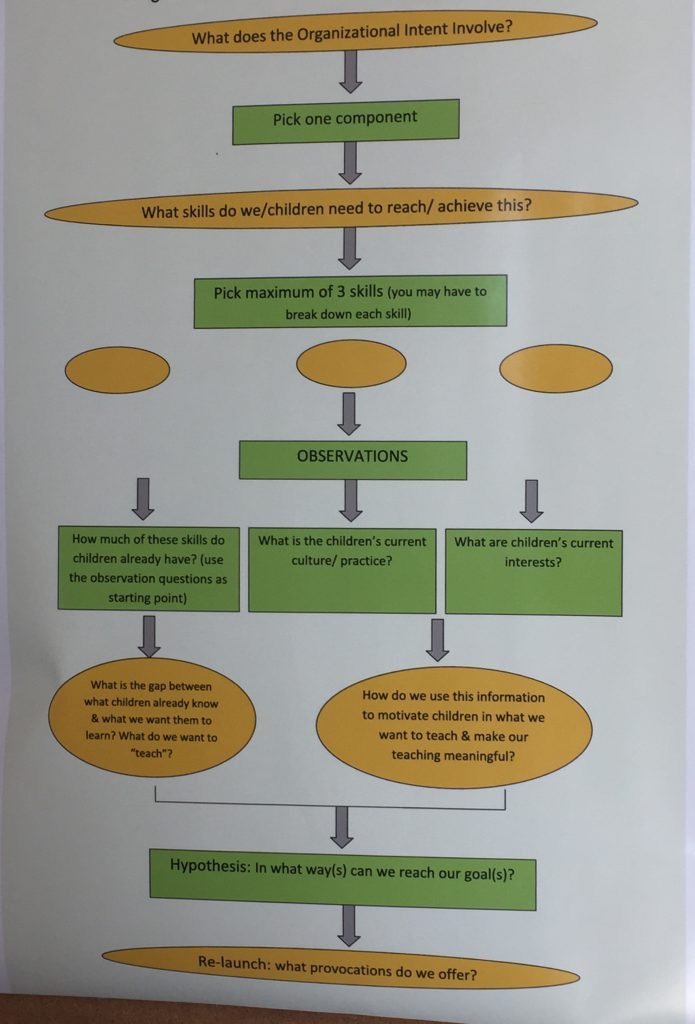

Similarly, the Reggio Emilia approach to Early Learning aims to engage children in rich learning experiences. Reggio invites children to engage in an area of learning holistically: by offering many different modes, presenting an assortment of tools and mediums, incorporating various locations and perspectives, by avoiding timelines, and by actively listening. However, unlike BC’s New Curriculum, Reggio Emilia centres follow an emergent curriculum. Though there may be a shared “intent” amongst several centres, “hypotheses” (focus of learning) are generally constructed by a community of learners based on observations of the needs, skills, values, interests, and challenges of a specific group of children. Below is the Reggio inspired curriculum pathway we follow at our centres:

In my previous post, I voiced the opinion that digital technology often rests on the periphery of the deep learning that takes place within the Reggio Emilia approach. However, as Apler (2011) suggests in her work, Developmentally appropriate New Media Literacies: Supporting cultural competencies and social skills in early childhood education, several of the New Media Literacies described by Jenkins et al. are already “reflected in the interplay between digital and non-digital media within Reggio Emilia-inspired teaching and learning” (Alper, 2011). In addition, if digital literacy happened to be a core component of an “intent” or “hypothesis” within a Reggio program, it would be approached with an aim to generate digital fluency.

Again, similarly, if BC educators regard digital literacy as pivotal knowledge for their learners than their learners should be thinking creatively and critically with and about it, they should be connecting, engaging, and collaborating with their peers through and with it, and they should be considering their personal well-being and the well beings of others with and in connection with it. However, as I highlighted in my post BC’s Stance on Digital Technology in Early Years Education digital technology is not explicitly outlined as an area of learning in either BC’s Early Learning Framework or in BC’s New Curriculum (K-5).

Therefore, perhaps BC’s Curricula and the Reggio Emilia approach are not so dissimilar with regard to their position on digital technology. Possibly, institutions within both locations are simply “slow to react to the emergence of this new participatory culture” (Jenkins et al., 2006). It seems clear that neither BC, nor Reggio Emilia, Italy consider digital literacy imperative for their young learners.

However, BC educator, Alison Galloway, also recognized the similarities between BC and Reggio Emilia, Italy, specifically with regard to BC’s movement towards a more child-centred approach to learning (Galloway, 2015). Drawing inspiration from the Reggio Emilia approach, BC’s education plan, and the “maker movement”, Galloway (2015) created a learning environment capable of generating rich teaching and learning experiences connected to digital technology.

In addition, in her MEd Project entitled Bringing a Reggio Emilia inspired approach up the grades- Links to 21st century learning skills and the maker movement, Galloway (2015) critically examined many of the same aspects of education as Jenkins et al. (2006). Galloway advocated for education that focuses on competency and values students’ voice and choice (Galloway, 2015), while Jenkins et al. promoted education that treats young people as citizens deserving of the skills necessary to become valued as such (Jenkins et al., 2006). Galloway wrote:

“If, as educators, we want children to be inventive and resourceful, we need to provide opportunities for open-ended learning that challenges students to come up with their own questions and solutions.” – Galloway, 2015

Still, Galloway’s (2015) research did not specifically focus on digital literacy, rather it outlined the potential value for teaching and learning generated within a Reggio Emilia inspired “Makerspace”.

It is my intent, however, to highlight the fact that the literature I have encountered with regard to the “maker movement” explicitly highlights the value of the approach in contributing to digital fluency or “critical literacy”.

Until next time,

EJ

References

Alper, M. (2013). Developmentally appropriate new media literacies: Supporting cultural competencies and social skills in early childhood education. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 13(2), 175-196. doi:10.1177/1468798411430101

Jenkins, H (2006). Confronting the challenges of Participatory Culture: Media education for the 21st century. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation: Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://www.oapen.org/download/?type=document&docid=1004003

Galloway, A. (2015). A reggio emilia inspired maker space. Retrieved from http://reggioinspiredmakerspace.weebly.com/reggio-emilia-background.html

Galloway, A. (2015). Bringing a reggio emilia inspired approach into higher grades- Links to 21st century learning skills and the maker movement. MEd Projects (Curriculum and Instruction): University of Victoria, BC.

Ministry of Education (2015). BC’s new curriculum. Victoria, BC. Retrieved from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca

Ministry of Education (2019). British Columbia early learning framework. Victoria, B.C. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

BC’s Stance on Digital Technology in Early Years Education

In my last post I suggested that incooperating digital technology into early years education is not a priority in BC. Is there evidence out there to support my assumption?

According to the government of BC website: “Digital literacy is an important skill to have in today’s technology based world.” The BC’s Digital Literacy Framework, first published in 2015, describes in detail what children age 5- 18 should be able to do, understand, and critically think about with regard to digital technology.

The framework outlines six main characteristics of digital literacy: research and information literacy, critical thinking, problem solving and decision making, creativity and innovation, digital citizenship, communication and collaboration, and technology operations and concepts. It also outlines some ways technology and digital resources might be incooperated into learning experiences for children age 5-8:

- Illustrate and communicate original ideas and stories using digital tools and media-rich resources. (C, T, CC, CI)

- Engage in learning activities with learners from multiple cultures through e-mail and other electronic means. (C, CC, TOC)

- Independently apply digital tools and resources to address a variety of tasks and problems. (T, CPD, TOC)

- Demonstrate the ability to navigate in virtual environments such as electronic books, simulation software, and Web sites. (TOC)

Despite the clear and expansive nature of the Digital Literacy Framework, BC does not specifically include digital technology in its Early Years curriculums.

Technology is not explicitly included within BC’s updated Early Learning Framwork Principles, though the principles do leave room for interpretation and the Framework itself promotes the incorporation of many modes for through which children can express and inquire. However, the Framework does include digital technology in Section Three: Living and Learning Together under the heading Communication and Literacies. Here the Framework highlights the fact that digital technology is part of most people’s everyday lives, that it can support and promote creative inquiry, and that there are complicated concerns surrounding its inclusion in the childhood experience.

And yet, digital technology appears to reside under Communication and Literacies only as a point for conversation and as a mode for communication. There are no specific examples provided in the Framework for how digital technology might be incooperated in Early Learning environments (besides its current primary use in Pedigogal Narration). Instead, it is suggested that educators take time to reflect on the potential creative and negative aspects of technology. It is clear that Early Childhood Educators and the BC Early Learning Framework are still pondering over whether digital technology should actually be included in Early Learning Environments.

BC’s New Curriculum defines technologies as tools that extend human capabilities and includes technology under the heading Applied Design, Skills, and Technologies K-7“. However, the term “computational thinking” becomes included under the heading “Applied Design, Skills, and Technologies” starting with 6 and 7. Computational thinking appears to be quite extensive and includes an awareness of coding, computer hardware and software (including troubleshooting), Internet safety, digital self-image, citizenship etc. By including specific learning outcomes regarding digital technology for the later grades, the BC Curriculum elucidates the expectation that British Columbian children be digitally literate, while at the same time it suggests that digital technology remain absent in Early Childhood.

It is clear, as I assume is the case with many of us graduate students, that British Columbia isn’t quite sure where it stands on the idea of digital technology in Early Learning. Such is not surprising as we currently live in a time that allows us access to a endless wealth of information, which generally leads us into an endless cavern of contradictions.

Until next time,

EJ

References

Ministry of Education (2015). BC’s new curriculum. Victoria, BC. Retrieved from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca

Ministry of Education (2019). British Columbia early learning framework. Victoria, B.C. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

Ministry of Education (2015). Digital literacy framework. Victoria, BC. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/teach/teaching-tools/digital-literacy?keyword=Digital&keyword=literacy&keyword=framework

Community